- Declaring that the judiciary cannot risk being caught in a “web of indebtedness” towards the government, the Supreme Court rejected the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act and the 99th Constitutional Amendment which sought to give politicians and civil society a final say in the appointment of judges to the highest courts.

- “It is difficult to hold that the wisdom of appointment of judges can be shared with the political-executive. In India, the organic development of civil society, has not as yet sufficiently evolved.

- The expectation from the judiciary, to safeguard the rights of the citizens of this country, can only be ensured, by keeping it absolutely insulated and independent, from the other organs of governance,” Justice J.S. Khehar, the presiding judge on the five-judge Constitution Bench, explained in his individual judgment.

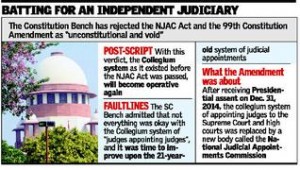

- The Bench in a majority of 4:1 rejected the NJAC Act and the Constitutional Amendment as “unconstitutional and void.” It held that the collegium system, as it existed before the NJAC, would again become “operative.”

- But interestingly, the Bench admitted that all is not well even with the collegium system of “judges appointing judges”, and that the time is ripe to improve the 21-year-old system of judicial appointments.

- “Help us improve and better the system. You see the mind is a wonderful instrument. The variance of opinions when different minds and interests meet or collide is wonderful,” Justice Khehar told the government, scheduling further debate for November 3 on bettering the working of the collegium system.

Bench feared a culture of “reciprocity” of favours

- While Justices Lokur, Kurian and Goel, agreed with Justice Khehar’s nearly 500-page ‘Order on Merits’ that the NJAC and the Constitutional Amendment defeated the primacy of judiciary over the government in the appointment of judges, Justice Chelameswar differed, saying that “judiciary cannot be the only constitutional organ capable of protecting the liberties of the people.”

- Justice Chelameswar disagreed with his fellow judges and upheld the validity of the Constitutional Amendment. In his exhaustive judgment approved by the majority on the Bench, Justice Khehar attacked the NJAC laws on merits, and said they would breed a culture of “reciprocity” of favours between the government and the judiciary, and thus, destroy the latter.

- Justice Khehar asked how future judges appointed under the NJAC can be expected to be independent-minded when the Union Law Minister is one of the six members of the Commission appointing them.

- “Reciprocity, and feelings of pay back to the political-executive, would be disastrous to the independence of the judiciary. [With] The participation of the political-executive, the selection of judges, would be impacted by political pressure and political considerations,” Justice Khehar observed.

- He said in a situation where government is a major litigant in the higher courts, this feeling of reciprocity may lead to disastrous consequences.

- The judgment said cases involving the government on sale and exploitation of natural resources through private entrepreneurs come to court. These are cases with “massive financial ramifications” and require judicial clarity of thought and fair mindedness.

- “Sometimes accusations are levelled against former and incumbent Prime Ministers and Ministers of the Union Cabinet, and sometimes against former and incumbent Chief Ministers and Ministers of the State Cabinets… Since the Executive has such a major stake, in a majority of cases, which arise for consideration before the higher judiciary, the participation of the Union Minister in charge of Law and Justice, as an ex officio Member of the NJAC, would be clearly questionable… One of the rules of natural justice is that the adjudicator should not be biased,” Justice Khehar observed.

Comments